Dear Reader (even those of you ponying up big bucks to harness the power of the Dark Side),

Missouri Sen. Eric Schmitt spoke at the National Conservative jamboree this week. He earned applause and scorn from all the usual corners. As a committed “both-sides” guy, I’ve come to you today to offer both.

Let’s start with some agreement.

“If you imposed a carbon copy of the U.S. Constitution on Kazakhstan tomorrow,” Schmitt proclaimed, “Kazakhstan wouldn’t magically become America. Because Kazakhstan isn’t filled with Americans. It’s filled with Kazakhstanis!”

He’s basically right. One reason we know this is that in the 19th century, many South American countries (Gran Colombia in 1821, Mexico in 1824, Chile in 1828) essentially did just that. It didn’t work out great for them.

Schmitt went on: “What makes America exceptional isn’t just that we committed ourselves to the principles of self-government. It’s that we, as a people, were actually capable of living them.”

I don’t think this is the best explanation of American exceptionalism, but I don’t really think he’s wrong, either. Early American culture was the product of a distinct, largely (but not entirely) English-infused worldview. But American culture was more than just Englishness. The Englishmen—and other Europeans—who came to the New World were self-selected in many ways. For instance, as Daniel Hannan writes in Inventing Freedom, “The Americas had largely been peopled by younger siblings. The grander families of Virginia—including the Washingtons—were known as the ‘Second Sons.’ Many of the younger brothers who had founded their lines in the New World had borne with them a sense of injustice that they had been denied any share of their ancestral lands through an accident of timing.”

Schmitt also says early on:

Now, let me just say: I believe that our Founding Fathers were the most brilliant group of men to ever assemble in one room. Their ideas are central to who we are. You can’t understand America without understanding things like the freedom of speech, the right to self-defense, the ideals of independence, self-governance, and political liberty.

But these principles are not abstractions. They are living, breathing things—rooted in a people and embodied in a way of life. It’s only in that context that they become real.

I agree in part and dissent in part. I agree that those ideas are central to who we are. But they are also abstractions, our abstractions, the abstractions that go a long way toward defining what it means to be an American. Russia, Iran, Japan, even Canada are peoples and nations, and their self-conception is bound up in ideas of what it means to be Russian, Iranian, etc. Those ideas aren’t all pure abstraction. Some are better understood as customs and practices. But scratch the customs and practices long enough and—ta-dah!—you’ll find ideas, abstractions, concepts, etc.

I’m going to come back to this, but the NatCons’ quintessential schtick is to create a false dichotomy between the abstract and the organic that allows them to claim they believe in our ideas while denying anyone who disagrees with them any right to being on the side of “real America.”

Let’s move on to the more serious disagreement.

Schmitt goes on to offer a potted Tucker Carlsonesque tale of the last few decades in which both the left and right conspired to vampirically bleed out American cultural heritage. The “Left took these principles and drained them of all underlying substance, turning the American tradition into a deracinated ideological creed. To live up to that American creed, they told us, we had to transform America itself.”

“On the right,” Schmitt informs us, “the situation wasn’t all that different.” By the 1990s, “too many on the Right had come to accept the same basic worldview as the liberal elites they claimed to oppose. In foreign policy, trade, immigration and the domestic culture wars, too many conservatives defined the American identity as nothing more than an abstract and vaguely defined proposition.”

A bit later he says, “For years, conservatives would talk as if the whole world were just Americans-in-waiting—‘born American, but in the wrong place.’ America was, as one neoconservative writer put it, ‘The First Universal Nation.’”

Now, I found this particularly intriguing. These are pretty obscure references. The “born American, but in the wrong place” line—which I’ve quoted often—is from my late friend Peter Schramm. And the neoconservative writer Schmitt is talking about is my old boss Ben Wattenberg.

I think this is a tendentious misreading of both Schramm and Wattenberg. Many people subscribed to American exceptionalism as much as Schramm and Wattenberg, but I don’t know anyone who believed in it more than they did. Schramm never argued that everyone in the world was “born American but in the wrong place.” That sentiment came from his father, who fled the Nazis and sought to live in America to escape tyranny. Here’s how Peter put it:

My father said that as naturally as if I had asked him what was the color of the sky. It was so obvious to him why we should head for America. There was really no other option in his mind. What was obvious to him, unfortunately, took me nearly 20 years to learn. But then, I had to “un-learn” a lot of things along the way. How is it that this simple man who had none of the benefits or luxuries of freedom and so-called “education” understood this truth so deeply and so purely and expressed it so beautifully? It has something to do with the self-evidence, as Jefferson put it, of America’s principles. Of course, he hadn’t studied Jefferson or America’s Declaration of Independence, but he had come to know deep in his heart the meaning of tyranny. And he hungered for its opposite. The embodiment of those self-evident truths and of justice in America was an undeniable fact to souls suffering under oppression. And while a professor at Harvard might have scoffed at the idea of American justice in 1956 (or today, for that matter), my Dad would have scoffed at him. Such a person, Dad would say, had never suffered in a regime of true injustice. America represented to my Dad, as Lincoln put it, “the last, best hope of earth.”

Now, Peter did believe that many people suffering under tyranny saw in America the same thing. The yearning for, and appreciation of, freedom is not a uniquely American thing. He just celebrated the idea that America was a symbol of, and refuge for, that yearning. I celebrate it, too.

Ben, a product of the Cold War, shared similar views. A big part of his argument about America being the First Universal Nation stemmed from his unbridled patriotic pride and belief in not just American exceptionalism but in the superiority of the American way. He passionately believed in America as that “shining city on a Hill.” He was indeed a vociferous defender of immigration (sometimes to a fault). But he was also a fierce believer in the importance of assimilation. He believed that immigrants—legal immigrants—were often the people most committed to what is best about America precisely because they chose to become Americans. Ben threw one party every year—on Flag Day. He was that kind of American.

Schmitt’s rendering of Schramm and Wattenberg’s motives, whether out of ignorance, laziness, or something more sinister, is little more than intellectual slander.

Abstract principles for thee, power for me.

The slander is in service to a larger argument, the one I referenced above.

This imagined left-right consensus—which he describes as a kind of conspiracy against real Americans—must be shattered. “That’s what set Donald Trump apart from the old conservatism and the old liberalism alike: He knows that America is not just an abstract ‘proposition,’ but a nation and a people, with its own distinct history and heritage and interests.”

I think this is a convenient misreading of Trump and what he “knows.” In Schmitt’s telling, Trump “knows that America is not just an abstract proposition.” That implies he thinks it’s somewhat an abstract proposition, and that’s a good thing. But does he? From everything we know about Trump, he’s either ignorant or contemptuous of those higher ideals. He thinks they make us weak and look like suckers.

Honestly, I’d be delighted if Schmitt’s version of Trump were true. Heck, I believe America isn’t just an idea. I believe it’s also a nation and a people. Where is the evidence that Trump subscribes to this both/and proposition?

When Schmitt says, “You can’t understand America without understanding things like the freedom of speech, the right to self-defense, the ideals of independence, self-governance, and political liberty” I nod along. But where’s the evidence Trump believes these things to the extent they should constrain his action or stand in the way of his will? He believes in free speech and political liberty for him and his friends, not so much for anyone else.

Schmitt, the NatCons, and many others in the New Right Popular Front love to talk about how our principles aren’t derived from abstractions plucked from the writings of John Locke. Fine. Indeed, as I argued in my last book, Locke’s Second Treatise on Government wasn’t nearly so influential on the founders as either Locke’s superfans or foes contend.

But so frickn’ what? If you want to argue that our principles emerged through Hayekian trial and error and have no connective tissue whatsoever to Locke, Adam Smith, Thomas Jefferson, or Edmund Burke, so be it. If you want to believe we derive them from midi-chlorians in the groundwater, knock yourself out. Aren’t they still principles?

Schmitt’s argument shows the intellectual rot of populism, because it rests on the idea that our principles matter only until they get in the way of what the populists want or what Donald Trump wants. Once they become inconvenient, we start hearing this boilerplate about the nation and the people and the need to do whatever “we” must do to win.

This is just another way of saying they’re not actually principles. If you believe in free markets, free speech, etc., only up and until the point they prove inconvenient, they aren’t really principles, are they? I believe in the principle that theft is wrong, but if I just take your bike because I really want it, then I don’t really believe in that principle. Then-Missouri Attorney General Schmitt believed—presumably—in free and fair elections until Trump lied about winning in 2020 and so Schmitt tossed those beliefs aside.

It’s funny: This week Sen. Tim Kaine invited well-deserved scorn for being shocked and appalled by the idea that our rights come from God and not from government. Pretty much everyone on the right partook in the dunking. But should Schmitt? If our rights come from God, not from the government—the material expression of “the people” and “the nation” after all—then our rights stem from—shudder—abstract principles. I’m not saying that theologically or in some other sense God is “just an abstraction,” but the claim that our rights come from God rests on literally abstracting ideas from that conviction.

Heritage Americans.

One last thing. Schmitt followed J.D. Vance’s lead by dabbling in the new hotness on the new right: the idea of “heritage Americans.” These are Americans who supposedly can claim more ownership of America and the policies it should follow because their ancestors got here earlier than more recent arrivals. Now, I share Schmitt’s scorn for the people who try to turn the story of America into an “expression of something perverse and evil.” On the other hand, his at times jingoistic celebration of America’s triumph and conquest over Indians and the continent as little more than a glorious expression of America’s right “to assert ourselves upon the world” has a will-to-power vibe to it. At times he makes our pioneer spirit seem like an exercise in American lebensraum with Andrew Jackson as a kind of avatar of the American spirit. One can love America and think the Trail of Tears wasn’t something to be proud of.

“My ancestors arrived [in Missouri] from Germany in the 1840s, during the first real wave of new European settlers since Missouri became a state in 1821,” Schmitt says proudly. “Back then, Missouri was as far west as you could go. Think about the kinds of people it takes to do that—to build a home at the edge of the known world. Those were the kinds of people our ancestors were.”

I have no doubt that they were made of sturdy Teutonic stuff. I also think my Slovak father-in-law who swam the Danube to escape the Communists a century later was made of similar stuff. So are the Vietnamese who came here in boats in the 1970s. And so was Peter Schramm’s Hungarian father.

Regardless, it’s worth noting that many of the Germans who settled in 1840s Missouri were refugees from the revolutions of 1848. I don’t know the specifics of Schmitt’s family, but the “48ers” moved to places like Missouri because they were on the side fighting for political freedom—liberalism, democracy, the rule of law, etc.— in Germany and they lost. So those European radicals came to America seeking the kind of freedom Americans understand as a birthright.

One might even call them Americans born in the wrong place.

The Missouri Germans were treated harshly by the “native” Missourians, mostly because the Germans were disproportionately opposed to slavery (80 percent of members of the early Missouri Union volunteer regiments were German Americans). And Missouri was a slave state.

That’s a heritage Schmitt might have boasted about: new Americans, fleeing persecution abroad and facing hostility from “heritage” Americans in their new home because the newcomers recognized the evil of slavery and sought to risk their lives fighting for those abstract ideals that drew them to America in the first place.

Schmitt opted for a different story.

Various & Sundry

Canine Update: There’s not too much to report this week. Zoë is doing fine, but she still is weirdly reluctant to believe me when I tell her I haven’t spiked her treats with iocaine powder. Pippa is even harder to rouse in the morning, I think because she’s getting creaky and feels it the most first thing. Don’t get me wrong, extracting belly rubs would still be a priority if she had an android body. But I think it’s a factor.

I know this is a common complaint of mine, but I really do take offense—and so does Pippa—when people don’t say hello or wave when the girls stick their heads out the car window and say hi to people in neighboring cars. I know this is kind of projection, but I’m still the kind of guy who always gets excited when I see a dog sticking his or her head out the window of a car and I always smile. I don’t get people who don’t. Clover did teach Pippa a new technique for getting her belly wet the other day, which Pip appreciated but Kirsten did not.

Anyway, all of the girls arewell-tended to, as is Chester the pesterer. Though on Tuesday morning I had to do the CNN 6 a.m. show and this meant that by the time I got back and took them out, Chester had been attended to before the crew had. They were pretty outraged by this breach in protocol

The Dispawtch

Why I’m a Dispatch Member: I’ve been a paying member of The Dispatch since Day 1. I deeply appreciate the business model of being honest about your intellectual priors, taking the time to conduct sober reporting, not chasing clicks, and so much more. Pretty sure I did a fist pump when you hired Kevin Williamson.

Personal Details: I’m a dog guy, always have been. Grew up breeding Brittanies with my dad. We’d teach them to hunt and point by casting a pheasant wing around the yard with a fishing pole, then let the dog loose to sniff it out. These days, I stick to rescues.

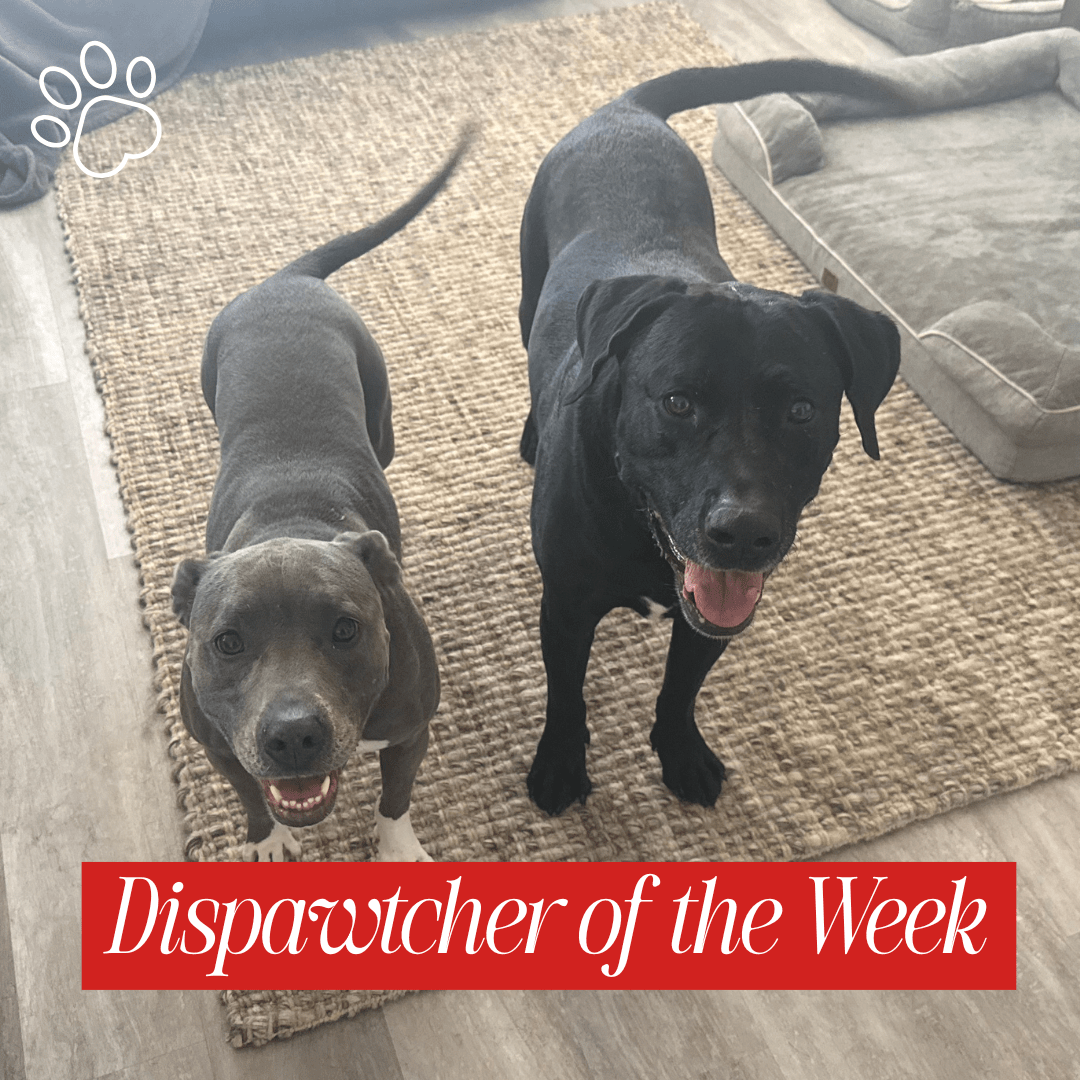

Pet’s Name: Zeke and Maya

Pet’s Breed: Zeke: Black lab/pit bull. Maya: Blue nose pit bull.

Pet’s Age: Zeke: 10.5 years. Maya: Almost 7 (we think).

Gotcha Story: I spent nearly a decade living in Hawaii. During my last six years there I was living on Maui. Zeke was found wandering around a sugar cane field outside the little town of Makawao. He was about 10 months old and the staff at the Humane Society insisted I meet this old soul of a personality. Fun fact: The lab/pit is a common mutt in Hawaii used for pig hunting. I call them Labrabulls.

We rescued Maya from the San Diego Humane Society almost three years ago to keep Zeke company since I could no longer take him to work with me after accepting a new job. It was a little dicey for the first few weeks, but they’re the best of friends now. Maya is our lovable resident velociraptor.

Pet’s Likes: Zeke: Chasing wildlife, wrestling like a UFC fighter with Maya (the old bull still has some juice), and lying at my feet. Maya: Wrestling with Zeke (her ground game is legit) and snuggling on somebody’s lap all day. She’d crawl inside you if she could.

Pet’s Dislikes: Both dogs are gun shy and do not like fireworks.

Pet’s Proudest Moment: Zeke: The time he managed to catch a fawn when we lived along the southern Oregon coast. It did not end well for the deer. Maya: She’s clearly had at least one litter of pups, so I would assume that. Since we’ve had her, I watched her destroy the highest density rubber Kong chew toy in less than 10 minutes.

A Moment Someone (Wrongly) Accused Pet of Being Bad: Haven’t had that one happen—yet.

Do you have a quadruped you’d like to nominate for Dispawtcher of the Week and catapult to stardom? Let us know about your pet by clicking here. Reminder: You must be a Dispatch member to participate.