Voters in California are deciding on a ballot measure labeled “Prop 50” that will determine new district lines to represent Californians in the state house and senate, as well as the U.S. House of Representatives.

The Democrat-led effort follows a successful redistricting process in Texas that left Lone Star Democrats with potentially five fewer congressional seats, and its constitutionality is being questioned by experts.

No accountability to voters, just special interests, lawyer says

“The legislature in California had to violate the California Constitution five different times in order to even put Prop 50 before the voters,” according to constitutional and election law attorney Mark Meuser with the Dhillon Law Group.

The California Constitution only allows mid-decade redistricting if voters pass a referendum or a court says the maps are unconstitutional, neither of which have happened. Meuser explained, “What Prop 50 does is create a third way where special interests in D.C. can get legislatures to draw new maps where they can create safe seats for their friends so that congressmen are not required to be accountable to the voters. When politicians are not accountable to the voters but accountable to special interests, we the people lose.”

On the surface, the process appears fair, but in reality, it is a system that artificially concentrates conservative voters into ultra-red districts while dispersing others into blue-leaning areas. Many argue that it is a strategic undermining of conservative influence in a state where Trump garnered nearly 38% of the vote in 2024, yet Republicans hold only 9 of 52 congressional seats (roughly 17%).

Saying the quiet part out loud

The ballot measure, which offers a simple “YES” or “NO” response, reads, “AUTHORIZES TEMPORARY CHANGES TO CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT MAPS IN RESPONSE TO TEXAS’ PARTISAN REDISTRICTING. LEGISLATIVE CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT.”

California’s current congressional district lines, redrawn after the 2020 Census and first implemented in 2022, shows how a supposedly impartial system can be manipulated to favor Democratic interests and marginalize Republican voices, or at the very least, used as a political tool of retribution and counter-attacks.

The ballot measure description reads: “Requires temporary use of new congressional district maps through 2030. Directs independent Citizens Redistricing Commission to resume enacting congressional district maps in 2031. Establishes policy supporting nonpartisan redistricting commissions nationwide. Fiscal Impact: One-time costs to counties of up to a few million dollars statewide to update election material to reflect new congressional district maps.”

The overtly partisan language may seem jarring, but according to Meuser, the racially-charged language used when debating the bill may be the most legally problematic aspect for supporters of Prop 50. According to Meuser, whose firm has taken statements from the debate and the result of the new maps, he believes the Prop 50 lines were drawn with race as a predominant factor, which could be easily challenged in court.

Ultimately, a Supreme Court ruling may tell all

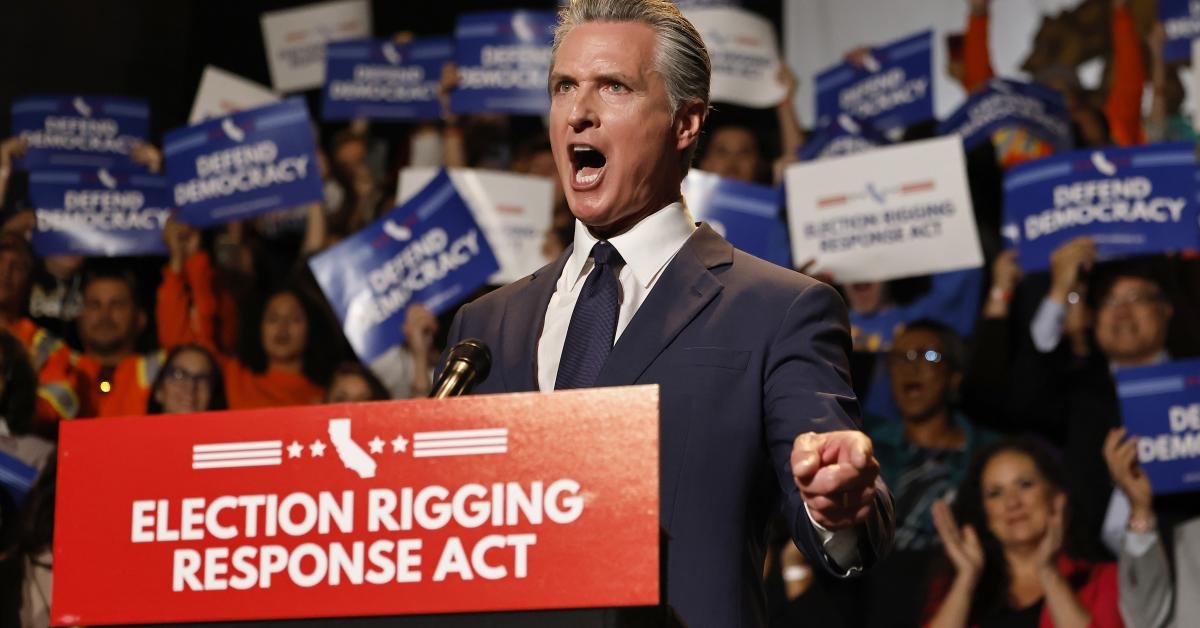

“California voters have the opportunity to vote down this unprecedented power grab by [California Governor] Gavin Newsom. Proposition 50 is an act that takes power from the people and gives it to special interests in D.C.”

California’s redistricting process was reshaped by voter-backed initiatives in 2008 and 2010, which stripped the Democrat-dominated Legislature of map-drawing authority and transferred it to the California Citizens Redistricting Commission (CRC). The CRC, a 14-member panel of ordinary citizens—5 Democrats, 5 Republicans, and 4 independents—is chosen through a randomized selection to prevent political insiders from dominating.

Tasked with prioritizing “communities of interest,” geographic compactness, and contiguous boundaries, the commission is prohibited from using partisan data. On paper, it’s a solid setup. Conservatives initially hailed it as a defense against the flagrant gerrymandering of the 1980s and 2000s, when Democratic operatives like Willie Brown and Phil Burton sliced up the state like a holiday roast to lock in safe blue districts.

Congressional district litigation is filed in federal district court, and the district judge must apply to the chief judge for the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, who will then appoint two more judges, one of which must be a circuit court judge, to form a special three-judge panel to rule on the case.

The decision of that three-judge panel is appealable directly to the Supreme Court, which is deciding the case of Louisiana v. Callais. Callais is a voting rights case, the result of which may either strike down or significantly narrow Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits racial discrimination in voting. A decision is anticipated before the 2026 election.