Imagine the president having the power to unilaterally cancel any expenditure that has already been enacted into law. A Democratic president could wake up one morning and decide to cancel all border patrol spending. Or to cut the defense budget by 20 percent. President Donald Trump could decide on a whim to eliminate Medicaid or veterans’ benefits. In an extreme case, Trump could announce before the 2026 midterm elections that he will cancel all Social Security and school lunch benefits for any congressional district that elects a Democrat. Or threaten to defund the Supreme Court if it rules against him.

Such a nightmare scenario would grant the president near-dictatorial powers over most government functions. Its evisceration of the separation of powers would be antithetical to the very foundations of the government crafted by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and other Founding Fathers. Americans would come to fear that every government program, and even the functional existence of Congress and the courts, depends on the daily will and wishes of the president.

This scenario is far less far-fetched than it sounds. These are the actual stakes in the Trump administration’s aggressive battle to legalize a practice known as “impoundment,” which occurs when a president refuses to implement federal expenditures that were authorized and appropriated by Congress and enacted into law. While no one disputes a president’s authority to veto spending bills passed by Congress (which can be overruled by a two-thirds congressional vote), nearly 235 years of constitutional interpretation, case law, and statute have made clear that—once a law is enacted—the executive branch is not permitted to refuse to execute that law. In matters of federal spending and the implementation of federal programs, impoundment would replace the rule of law with rule by one person.

Impoundment is unconstitutional.

Article 1, Section 9 of the Constitution clearly gives Congress the power of the purse, stating, “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.” And rather than grant presidents the authority to refuse implementation of such expenditures, the Constitution mandates that the president “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.”

Historically, presidents have occasionally taken advantage of statutory spending flexibilities or canceled a few small projects that even Congress usually agreed were no longer necessary (this limited flexibility was eventually blessed within the Antideficiency Act). Yet in 1973, President Richard Nixon attempted to impound billions of dollars of enacted clean water appropriations over the objection of Congress. In doing so, he declared, “The constitutional right for the President of the United States to impound funds … is absolutely clear,” and therefore, “I will not spend money if the Congress overspends.”

The Supreme Court disagreed, unanimously, leading Justice Antonin Scalia to summarize decades later that: “President Nixon, the Mahatma Gandhi of all impounders, asserted at a press conference in 1973 that his ‘constitutional right’ to impound appropriated funds was ‘absolutely clear.’ … Our decision two years later in Train v. City of New York, 420 U. S. 35 (1975), proved him wrong.” Scalia’s words appeared in the Supreme Court’s 1998 decision striking down President Bill Clinton’s use of a line-item veto, which attempted to block certain portions of a spending bill in a manner that was also tantamount to impoundment.

Nixon should have listened to his own assistant attorney general (and future chief justice), William Rehnquist, who had advised him that the “existence of such a broad [impoundment] power is supported by neither reason nor precedent,” and thus “It is in our view extremely difficult to formulate a constitutional theory to justify a refusal by the President to comply with a congressional directive to spend.”

Nixon’s impoundment prompted not only the Supreme Court’s 9-0 decision in Train v. City of New York, but also Congress’ passage of the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974. This law, ultimately signed by Nixon, sprinkled a statutory impoundment ban on top of the existing constitutional prohibition and codified a formal rescission process whereby the president can request that Congress vote to cancel an enacted expenditure before it is made.

Trump defies impoundment law.

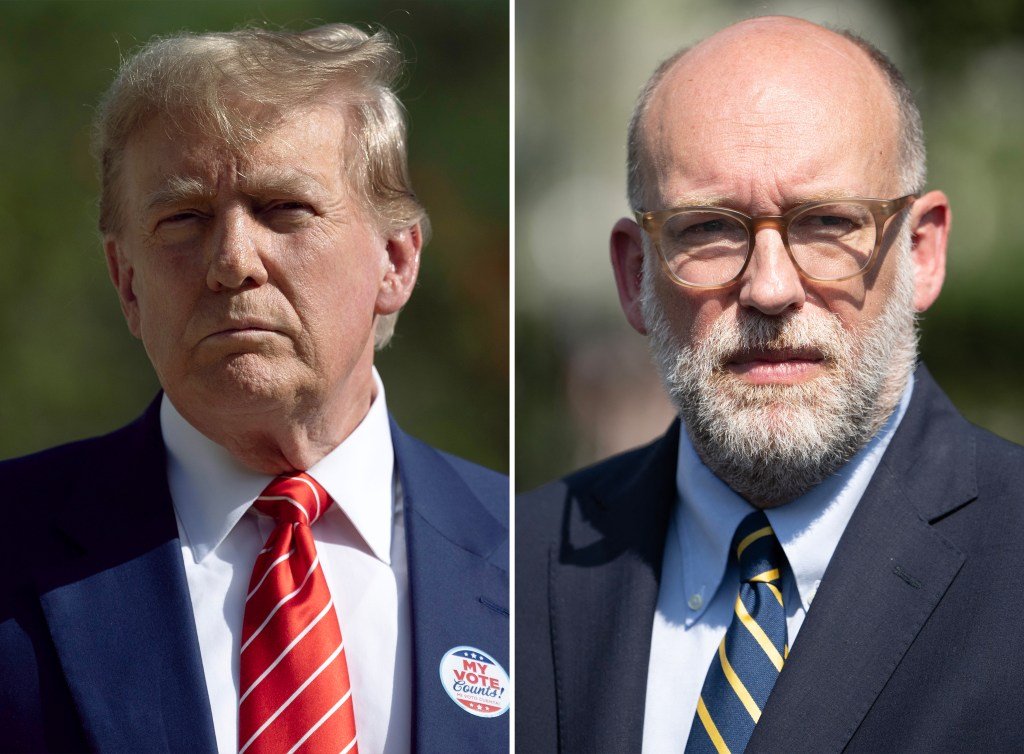

Five decades later, the Trump administration claims that the Constitution guarantees its right to impoundment, and that Congress’ 1974 statutory ban was unconstitutional. Campaigning last year, Trump pledged to “use the president’s long-recognized Impoundment Power to squeeze the bloated federal bureaucracy for massive savings” and to “restore executive branch impoundment authority to cut waste, stop inflation, and crush the deep state.” On Inauguration Day this year, he signed an executive order to “immediately pause the disbursement of funds appropriated through the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (Public Law 117-169) or the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (Public Law 117-58).”

DOGE director Elon Musk publicly pledged to ignore impoundment restrictions, and immediately began unilaterally cancelling foreign aid, public health, and other funding that had been appropriated and signed into law just months earlier. (Trump’s occasional victories in resulting lawsuit have largely rested not on impoundment’s ultimate constitutionality, but rather on questions of who has standing to file suit against impoundment or whether the funding may be paused while the lawsuits are proceeding.) The White House also illegally took down a publicly available apportionment database to hide its additional impoundments from Congress and the American people. A federal court recently required that the database return online, which revealed the additional impoundments.

The Trump administration’s legal arguments for impoundment range from flimsy to nonexistent. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) general counsel Mark Paoletta co-authored a 2024 article claiming that—as the head of the executive branch—the president has almost limitless freedom to decide which laws to implement and how to implement them. Paoletta is arguing, essentially, that nearly all congressionally enacted laws are merely suggestions and guidelines that give the president and executive branch substantial discretion to follow, alter, or disregard—no different from deciding whether to prosecute certain crimes or which enemy cities to bomb during a war.

Of course, those flexibilities around prosecutions and war strategy exist because the underlying constitutional provisions and enacted statutes do not micromanage such decisions. Yet the vast majority of current spending laws contain no language making them optional. And while past Congresses typically went along with presidents canceling the occasional small appropriation that was no longer necessary (such as new weapons to combat a military threat that suddenly ends), no president claimed broad, essentially limitless impoundment authority until Richard Nixon. And he lost 9-0 at the Supreme Court and inspired the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974.

The Trump administration’s most common impoundment defense is not a legal argument at all. It simply asserts that President Trump was elected by the American people with a broad mandate to eliminate wasteful spending and balance the budget by any means necessary. Of course, presidents take an oath to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” And there is no “presidential mandate” exception to the Constitution—only a (purposely) challenging amendment process.

If President Trump, OMB, and DOGE continue to accelerate their impoundment push, it may create (yet another) constitutional crisis. Such a move would essentially eliminate Congress’ power of the purse and cut it out of the budget process. (One wonders whether a Congress that has already surrendered its authority over foreign policy, trade, and DOGE would even bat an eyelash at losing one of its most important remaining powers.) If the president insists on impounding more funds, key questions include who would have standing to file a lawsuit, whether intimidated federal courts would enforce the constitutional ban on impoundment, and whether the Trump administration would even comply with a court-ordered ban. These are surreal questions to be asking in 2025.

Impoundment will not fix budget deficits.

Setting aside the legalities—an admittedly dangerous thing to do—should fiscal conservatives cheer the concept of impoundment? After all, annual federal spending has soared past $7 trillion, annual budget deficits are approaching $2 trillion, and no one disputes that the federal budget includes significant amounts of wasteful and unnecessary spending. Why shouldn’t we want our presidents to bypass our do-nothing Congress and take an axe to the budget?

First, impoundment is anti-democratic. A Congress that loses its authority over federal spending—after already surrendering its authority over foreign policy and trade—would barely exist as a functional branch of government. Congress’ vital democratic roles include ensuring that more local communities have a voice in federal spending decisions. And distributing this power across 435 House districts and 100 Senate seats with diverse constituencies promotes compromise, moderation, and open debate. Moreover, electing House members every two years and senators on staggered six-year schedules ensures a balance between respecting the voters’ current passions and giving some voice to the differing national moods that prevailed in the previous two election cycles. After all, most presidential parties do poorly in midterm elections because an unsatisfied electorate wants to put more checks on the current president—including in budget policy.

By contrast, vesting too much power in one person elected every four years would turn presidential elections into an even higher-stakes exercise to choose a four-year dictator. A razor-thin presidential race like in 2000 should not swing the pendulum between a left-wing and right-wing budgetary dictatorship.

Second, impoundment is chaotic. Voters should be able to expect some basic level of policy continuity regardless of a particular election result. Imagine retiring knowing that your Social Security and Medicare benefits could be canceled at any point if the wrong party wins the White House or the president gets heckled at an AARP event. Depending on which party wins the presidency, defense could be dangerously defunded, border spending terminated, SNAP benefits cut off, or federal prisons emptied based entirely on presidential whim. Yes, no federal spending is ever permanently guaranteed, and all programs are vulnerable to a wave election. However, passing drastic reforms (particularly through the Senate) requires a broader national consensus across more than one election cycle. The nation cannot be blindsided and its government held hostage by a single elected official acting without warning.

The potential chaos does not stop there. Depending on the strength of the Constitution’s equal protection clause, unlimited impoundment may allow a president to suddenly cancel a state’s infrastructure projects as retribution for voting for the losing presidential candidate. Or to target certain congressional districts, cities, or demographics for the elimination of government benefits. If such scenarios sounded absurdly implausible and paranoid for most of modern American history, they certainly are less so in 2025.

Finally, impoundment would likely not cut much spending—and may even increase it. DOGE has shown that presidential authority to unilaterally cut spending does not necessarily bring a broader war on budget deficits. Instead, DOGE achieved mostly symbolic savings by defunding MAGA’s targets such as DEI contracts, Politico subscriptions, government employees, and foreign aid. In fact, DOGE’s attempt to fire IRS tax enforcement staff will likely expand budget deficits by encouraging tax evasion and limiting the resources to investigate it. Presidents do not get elected promising to impose budget cuts on their own voters, and spending cuts targeting smaller electoral minorities (or foreigners) are unlikely to fix annual budget deficits headed toward $4 trillion within a decade because of the costs associated with Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, defense spending, veterans, and paying interest on the debt.

Moreover, a legal framework that grants presidents unlimited power to cut spending may well provide accompanying powers to expand spending, too. After all, we are describing a world in which common-sense constitutional restraints have broken down, so it is not difficult to imagine the spending flexibility going in both directions. In that scenario, what better way to reward the last election’s voters and bribe those in the next election than by promising Santa Claus-style entitlements, tax credits, infrastructure, and education spending? It should not surprise anyone that removing politicians’ fiscal restraints has tended to expand deficits rather than reduce them.

Again, these scenarios may sound like the stuff of fantasy. Yet from President Barack Obama’s “pen and phone” use of executive orders, to President Joe Biden’s illegal student loan bailouts, and now to President Trump’s impoundment push, we’ve seen how presidents will ultimately stretch any presidential powers in ways that once had barely been imagined. The question is whether it is wise to trust President Trump and his White House successors with an impoundment power strong enough to shatter the separation of powers.

A better way forward.

The case against impoundment is not a case for runaway spending and deficits. Trump has already cut spending by $9 billion by using his legitimate rescission authority to send Congress a list of enacted expenditures that he would like the House and Senate to repeal. This rescission power could be strengthened by requiring that presidential rescission requests receive a standalone House and Senate vote even if lawmakers would rather ignore them (a proposal known as “expedited rescission”). Additionally, Congress is free to specify that certain appropriations give the executive branch discretion to spend less than the appropriated amount. Finally, Congress could enact more sequestrations into budget law, whereby spending and deficit overages trigger automatic across-the-board spending cuts. These options are legal because they do not override Congress or the enacted language in spending bills.

Ultimately, the central barrier to major spending and deficit reduction is “we the people.” Voters punish any politician who even suggests addressing the growing Social Security and Medicare shortfalls, raising taxes, or skimping on spending priorities such as defense, veterans, border control, safety net, education, and infrastructure. The electorate demands that elected officials provide endless tax cuts, more spending, and somehow a balanced budget. The answer to runaway spending is not to eviscerate Congress and the vital separation of powers, but rather for voters to participate more responsibly in our representative democracy.