You’re reading the G-File, Jonah Goldberg’s biweekly newsletter on politics and culture. To unlock the full version, become a Dispatch member today.

Dear Reader (including any recently apprehended chair thieves),

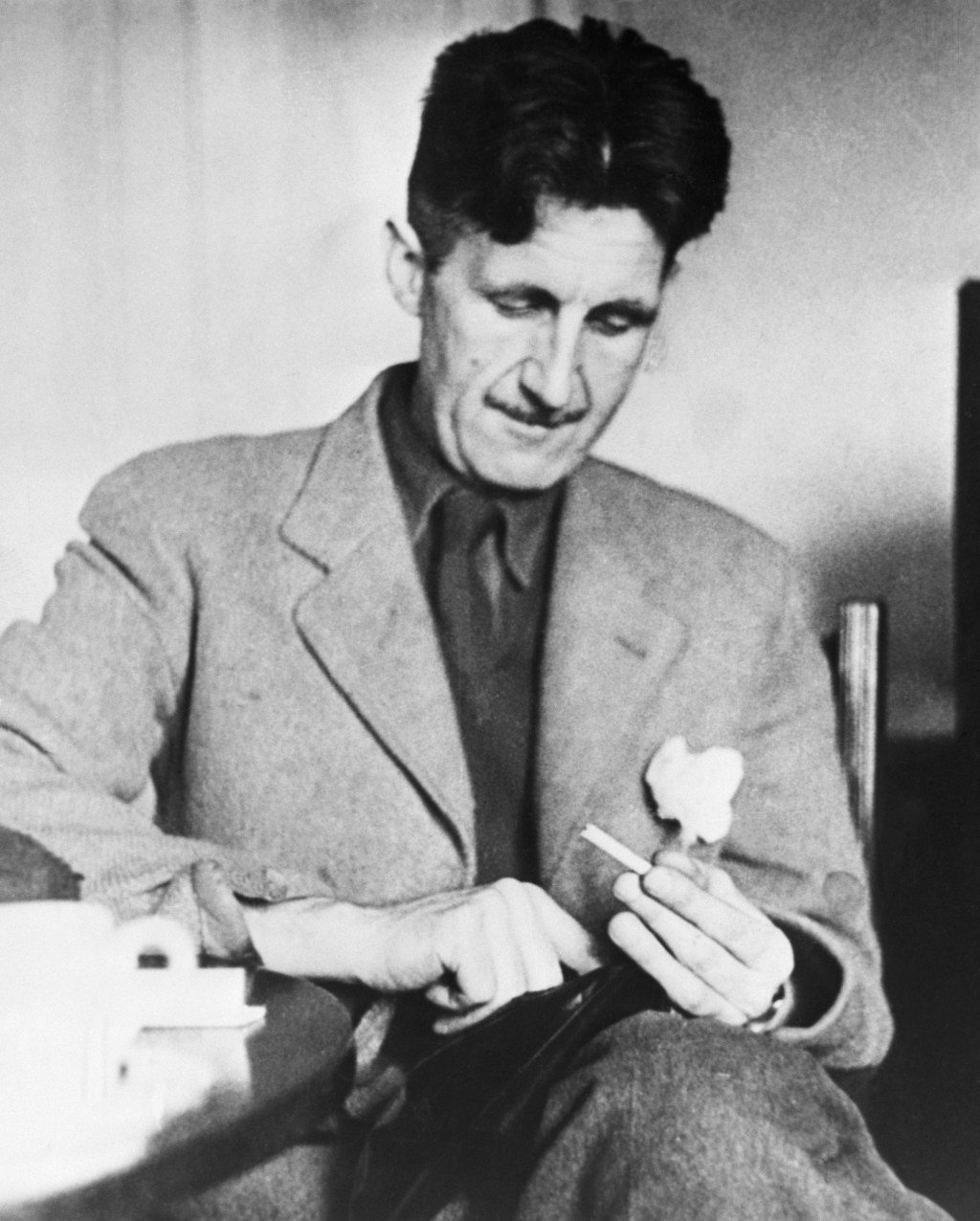

If I had to pick a single piece of writing that captures the state of American political culture today, it would be an essay published 80 years ago this month: George Orwell’s “Notes on Nationalism.”

I’ve long argued that Orwell was the first and, in my opinion, the best intellectual to spot the problems with identity politics. It was an even more impressive feat, given that the term “identity politics” didn’t emerge until the 1970s.

Orwell admits the handicap from the outset. He begins the essay:

Somewhere or other Byron makes use of the French word longueur, and remarks in passing that though in England we happen not to have the word, we have the thing in considerable profusion. In the same way, there is a habit of mind which is now so widespread that it affects our thinking on nearly every subject, but which has not yet been given a name. As the nearest existing equivalent I have chosen the word ‘nationalism’…

What Orwell meant by nationalism wasn’t “patriotism.” Rather, he wrote:

By ‘nationalism’ I mean first of all the habit of assuming that human beings can be classified like insects and that whole blocks of millions or tens of millions of people can be confidently labelled ‘good’ or ‘bad’. But secondly – and this is much more important – I mean the habit of identifying oneself with a single nation or other unit, placing it beyond good and evil and recognizing no other duty than that of advancing its interests. [emphasis mine]

His peculiar nationalism “does not necessarily mean loyalty to a government or a country, still less to one’s own country, and it is not even strictly necessary that the units in which it deals should actually exist.” Rather it’s a cause, an abstraction, an idea, that confers a sense of belonging and membership to the exclusion of other sources of identity.

I’ve heard many actors explain how putting on a costume—a suit of armor, a Victorian dress, Viking furs—allows them to inhabit the character. Orwell’s nationalism is this kind of identity. It’s a uniform that empowers you to play a part. It lets you be the cause you’ve committed to.

This is how what we call identity politics works. The identity is the cause, and the cause is in you. Identity—or, again, “nationalism” in Orwell’s telling—gives you permission to say or do things that you normally wouldn’t because the identity defines what is to be done.

On the right—and in certain class-focused traditions of the left—identity politics is a term reserved almost entirely for race, sex, and sexual orientation. It’s what the gays and the blacks and the bra-burning feminazis do, but not “us.”

This points to why the Orwell essay is so useful. It was written not only before the advent of the term “identity politics,” but before these familiar forms of identity politics came to define the term. But Orwell’s whole point is that this mode of thinking is much larger than that. It definitely applies to what some call “identitarians” of race or sex. But it also applies to many opponents of such people. Indeed, it applies just as well to many of today’s nationalists.

The word we seem to have settled on to describe what Orwell meant by nationalism and what we sometimes mean by “identity politics” is tribalism. In his magnificent book, The Tribal Imagination, Robin Fox (borrowing a bit from David Barash) describes how the “tribal humans of the Old Stone Age brought all [of their evolutionary] baggage and more with them, and it was molded then into the behavioral and cognitive repertoire of modern humanity. But none of it was lost. We do not lose anything in evolution, even if we do sometimes times reduce it to a Whisper, or a very quiet Drumbeat.”

Tribalism is the first safe harbor, the original home base. We have “coalition instincts” that find safety in numbers. During times of stress, we seek security in teams, and the internal morality of teams is different than the morality of the external world. We forgive or ignore transgressions by members of our own team that we not only condemn in other teams, but that we use as rationales for why that team is bad and ours is good.

Joe Biden’s corruption (real and alleged) was denied or ignored by his team, but for many on the right, his corruption virtually defined him and his team. Donald Trump’s corruption (real and alleged) is denied or ignored by his team, but it virtually defines Trump and his defenders for many on the left.

Left-wingers on the identitarian left say horrendous things about white people and “whiteness” and the broader left ignores, contextualizes, dismisses, meekly dissents, or quietly nods. Right-wingers on the identitarian right say vile things about blacks (or Jews, Indians, Hispanics, etc.), and the broader right works from the same menu of responses. On either side, to forcefully and forthrightly condemn the statements of your own team is a far worse transgression than the statements themselves.

For many on the left, right-wing violence is conclusive evidence of the broader right’s perfidy, but left-wing violence is either an irrelevant anecdote or a misguided but understandable expression of justifiable rage. And vice versa.

I am disgusted by the binary worldview that sees their racism or antisemitism as proof of villainy, but our racism or antisemitism to be inconsequential and irrelevant when stacked against the need for unity in the cause (J.D. Vance condemns hateful and violent rhetoric by them but considers condemnation of hateful and violent rhetoric by us to be mere “pearl clutching” that distracts us from the cause).

If the cause requires solidarity with evil, then the cause is the problem. The standard cannot be “but they’re worse!”—even when it’s true. Lesser evils are still evils.

While man’s capacity for evil can never be denied, the primary driver of these competing hypocrisies is not deliberate moral depravity—very few villains ever think they are the villain in their own story—but the unintended moral depravity that excessive loyalty inspires. That’s the problem with the tribalism of identity. It elevates loyalty to the top of the moral hierarchy. When you make loyalty the highest good, then loyalty becomes the instrument of devotion to the cause. As Leon Wieseltier once observed, “It is never long before identity is reduced to loyalty.”

Loyalty can indeed be noble. But it can also be an excuse for participating in evil. Like unity, the morality of loyalty is wholly determined by the object of the loyalty and the conduct that loyalty inspires. Evil done out of loyalty to a good cause is still evil. And decent conduct in furtherance of an evil cause does not excuse the evilness of the cause. All things being equal, I think loyalty is a good thing, but it is never the best thing, never mind the only thing. And when you make loyalty your north star, you are blinding yourself to more important things.

The point is that as soon as fear, hatred, jealousy and power worship are involved, the sense of reality becomes unhinged. And… the sense of right and wrong becomes unhinged also. There is no crime, absolutely none, that cannot be condoned when ‘our’ side commits it. Even if one does not deny that the crime has happened, even if one knows that it is exactly the same crime as one has condemned in some other case, even if one admits in an intellectual sense that it is unjustified – still one cannot feel that it is wrong. Loyalty is involved, and so pity ceases to function.

When I began, I referred to the “state of American political culture.” I didn’t say the “state of American politics.” Because this isn’t politics, rightly understood.

Let’s go back to Aristotle. He viewed politics as the science of how human beings can live well together. It is not merely about power or administration but about creating the conditions for virtue and the good life (eudaimonia) within a community. The founders were deeply influenced by this conception of politics. They were also fully aware of man’s tribal nature.

What they could not envision was that mere partisan identity could be nationalized—both in the conventional sense and in Orwell’s. They didn’t really anticipate formal organized parties at all. Following Burke they used the word “party” more figuratively than literally because the modern organizations we associate with the term basically didn’t exist at the time. A party was an informal group or faction in favor of a specific policy—as in “the war party.” They did know that factions were inevitable and constructed the Constitution to deal with that inevitability.

But the idea that a party-affiliation would become a tribal identity one put ahead of one’s other interests was beyond their imagining.

That form of identity or Orwellian nationalism is the chief problem with our political culture, but it is not the only one. The craving for what we call identity is the symptom or byproduct of a deeper need: to find meaning.

The trouble with the quest for meaning is that at its core, meaning is a binary star. We all want to be recognized as an individual, a unique person worthy of admiration. But we also want to belong, to be on a team, part of a community. The tribalism Orwell called nationalism is like a synthetic drug that offers a cheap substitute for the real thing. The cause substitutes for community, and one’s performative loyalty to the cause substitutes for individuality. Being the most committed to MAGA, or the Resistance, or Communism, Nationalism, Fascism, Feminism, This-ism or That-ism, scratches the itch for individual recognition while the “ism” fills the community-shaped hole in your soul.

The problem is that this methadone of meaning can’t really do the job. The high doesn’t last. So, like addicts are so wont to do, they up the dosage. And, like the addict who eventually ruins relationships, steals from his family, and is lost in pursuit of one thing over every other thing, political addicts lose their humanity, too.

The answer to craving isn’t some singular ideological identity, but multiple identities, multiple sources of meaning, multiple outlets for individuality. In your family you are one person—or one facet of your character is preeminent—in your work, another. Among your friends yet another. At church you may be a follower, but at work you are a leader. Or vice versa. Or a little of both. Your attachments should be varied too. There’s nothing wrong—and much that is right—with caring more for your local community than your country.

This is the vision that the founders bet the republic on. A vast nation comprised of diverse communities, faiths, interests, ambitions, and even more diverse conceptions of meaning and identity. Politics is supposed to be the mechanism by which these different entities and individuals work out how to reconcile conflicts and maximize the ability for individuals to pursue happiness. As I often say, the pursuit of happiness is an individual right, but it is most often, and best, realized in a community.

The core problem with our political culture is that too many people—and certainly the loudest and angriest ones—think that community is the whole nation and that every institution within it must conform to a single Orwellian-nationalist conception of how to live—and think. When such voices control our parties, leading institutions, and the federal government, politics ceases to be politics rightly understood. Instead, it becomes a war of tribes and tribal visions of us versus them. And as with so many wars, refusing to participate, or simply refusing to show sufficient ardor for the fight, is seen as a sin in the new religion. Because, again, when loyalty to the cause is the highest form of morality, all of the other moralities vanish or become merely situational.

Thanksgiving is coming and with it the inevitable articles about how to get along—or not!—with relatives who have different politics than you. I hate most of these pieces because they assume that your political identity is who you are. Like the actor who wears a costume to better realize a role, they want people to wear their costumes home over the holidays. Worse, they assume that the relatives and friends at your Thanksgiving table are defined by their politics, too. That their costumes are just as permanent as yours.

I take politics very seriously. I make my living from it. But the suggestion that I would reduce my family members to their political or ideological commitments is to suggest that I no longer see them as family. This same logic applies to the ever-expanding circle of relationships and commitments we have outside of the family, friends, neighbors, co-workers, co-religionists, etc. The further out you go, there’s more room for politics to matter, but even then, other things should still matter.

But family is where that binary star of meaning is born. In our families we are unique and valued, and we are part of something bigger than us. We are owed, and we owe. We need and are needed. We sacrifice for family and families sacrifice for us. When our nationalized political culture forgets or denies that, then it is the political culture that is broken. And the people who say otherwise are probably a little broken, too.

Various & Sundry

Canine Update: Gracie’s hose water addiction endures. The girls are happy. The watchful Dingo loves a good stakeout and a good aroo. Appeasement continues. And Fafoon’s gaze still inspires fear. At the beginning of the week, I had to go up to NYC for the Commentary Roast, which was great fun. The dogs were very upset about my departure (TFJ was already out of town), but they had a fun sleepover at Kirsten’s, where even Pippa tried her hand as a watchdog.

The Dispawtch

Member Name: Cleve

Why I’m a Dispatch Member: I was listening to The Remnant just about every day and thoroughly enjoyed the depth, breadth, and great interviews. I figured I’d subscribe to The Dispatch for access to other like-minded writers and sharp content and have been quite satisfied.

Personal Details: I’m pretty much a lifelong small-l libertarian and have been troubled since 9/11 about growing executive power, Congress abdicating its duties, and the like. Things seem to be reaching a crescendo now. Happy there are folks at places like The Dispatch trying to fight the battle of ideas, saying what needs to be said, and trying to cultivate an audience without any fear.

Pet’s Name: Rosie

Pet’s Breed: Mutt

Pet’s Age: 8

Gotcha Story: Rosie is a rescue from a shelter. She was a stray before. We’re sure she was abused, as she is fearful around strangers, especially men, until proven safe. The exception being dog people—she seems to recognize them as many dogs do and warm up quickly.

Pet’s Likes: Toddler-supplied floor food. All scents on all bushes and all blades of grass, especially if evidence of canine engagement with said items.

Pet’s Dislikes: Bikes, strangers, purebreds or probably just confident-looking dogs in general, and waking up from naps.

Pet’s Proudest Moment: I’ve never seen a dog with such a sense of smell. She’s amazing. She’s pulled me off on multi-block, seemingly random gallivants culminating in a hunk of bread waiting in someone’s front yard. Amazing. I suspect she learned it on the streets.

A Moment Someone (Wrongly) Accused Pet of Being Bad: Like I said—she has a great sense of smell and likes street food. Well, she found an extremely decayed raccoon in the woods behind our house, rolled herself all over it, and developed a lovely aroma. I had to take her into our basement and get her straight in the shower. Good times! Good dog!

Do you have a quadruped you’d like to nominate for Dispawtcher of the Week and catapult to stardom? Let us know about your pet by clicking here. Reminder: You must be a Dispatch member to participate.

ICYMI

—Trump can now kill whoever he wants

—Star Trek and whales

—Looking for Vance’s conversion story

—Why George Washington was awesome

—Trump = WMD

—Lies and authoritarians

Weird Links

—An ovine march

—Naked cyclists teach Trump a lesson

—Little-lion surplus in Cyprus

—Oregon pumpkin shenanigans

—Wild crocodile chase